Today’s per capita alcohol consumption in the UK is much lower than ten years ago. At the same time, however, the number of people dying from harmful consumption patterns of alcohol ended up broadly at the same level last year than it had back a decade earlier. In fact, according to data published by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) in December, the UK’s alcohol-related death rate seems to have increased slightly in 2017, with fatalities rising to 7,697 – the highest level recorded since 2008.

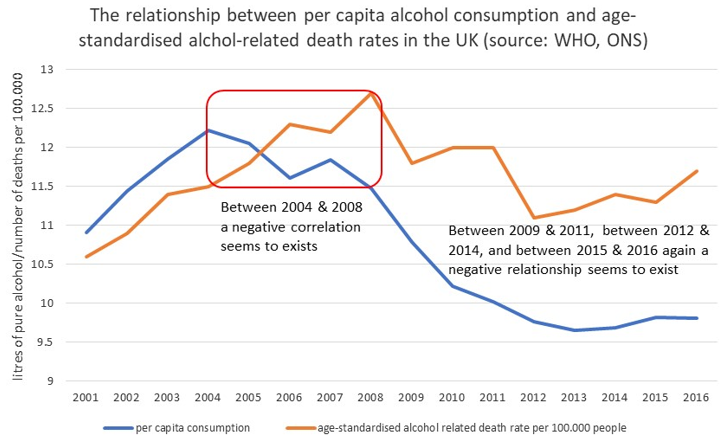

The fact that per capita alcohol consumption seems not to be directly linked to alcohol-attributed deaths is a remarkable finding. It puts a strong question mark behind the claim put forward by many public health advocates and NGOs that per-capita alcohol consumption is one of the most compelling and valid indicators when discussing effective measures on how to reduce alcohol-related harm.

Proponents of the claim have been quick to point out that, in the fight against harmful consumption of alcohol, priority should be given to broad, population-based measures, such as price policy measures to reduce overall per capita alcohol consumption. However, in light of the above findings, such broad and undifferentiated measures would not seem to be ‘best fit’ to render the desired results in terms of reducing alcohol-related deaths in the UK.

So what are the lessons to be drawn? To answer the question, it is essential to look at the details. In the UK, well over 70% - and thus the vast majority - of consumers of alcohol are light-to-moderate drinkers. As such, they tend not to die from alcohol-related causes such as chronic liver cirrhosis or mental disorders (the latter being typically the result of longer-term and extreme alcohol misuse). The chart below illustrates the absence of a direct, immediate link between per capita alcohol consumption and alcohol-related death rates in the UK over the last 15 years.

The fact that alcohol-related deaths are rising again in the UK is undisputable. It presents a serious public health issue that deserves serious and adequate evidenced-based policy responses.

However, when seen against the background of the reduced per capita consumption in the UK, it would seem that broad, population-based policy measures which do not differentiate between different drinking patterns are probably not the tool of choice.

This is significant in the sense that it makes it hard to justify the argument that the majority of moderate drinkers should pay (via higher prices and excise duty rates, for example) for a policy measure aimed to reduce per capita consumption when this approach does not really seem to help the minority group that suffers, and dies from, alcohol-related harm.

Ramping up prevention measures has to be an essential part of any policy response to reduce alcohol-related harm. Yet instead of focusing on a blunt reduction of per capita consumption, priority should be given to focused and differentiated measures that effectively reach current at-risk drinkers and help extreme drinkers to get out of the risk zone.