Introduced in Scotland in 2018 at a rate of 50p, MUP establishes a minimum price at which one unit of alcohol can be sold. Given the uncertainty of the effects, MUP was introduced with a “sunset clause”, meaning that the legislation would need to be repealed by the end of April 2024, if it did not show a reduction in alcohol-related harm. Despite an arguably thin – and partially negative and ethically problematic evidence-base – the Scottish Government announced last week that the rate would increase from 50p to 65p per unit. The move underlines once more that MUP should rather be viewed as a political pet project, than viewed a solid evidence-based public health policy intervention.

Public Health Scotland’s 2023 report

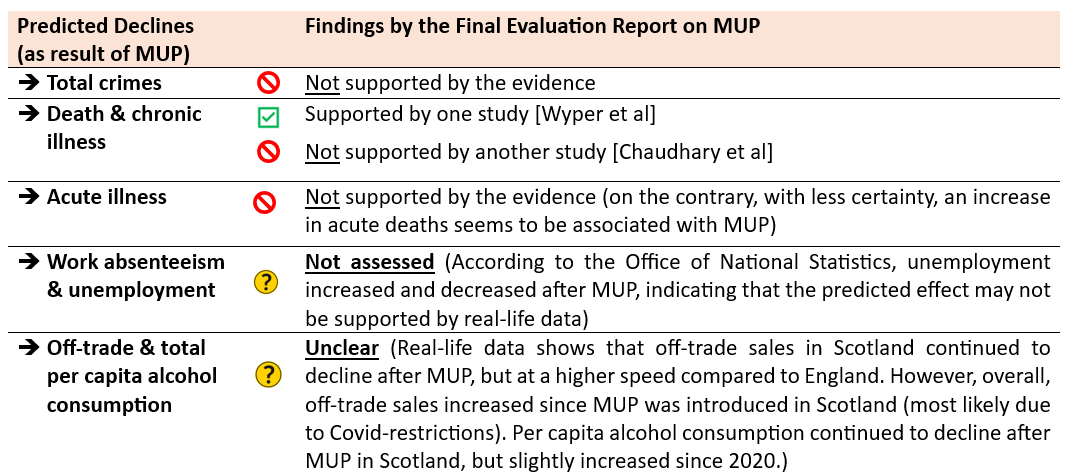

Last year, Public Health Scotland’s Final Evaluation Report on MUP focussed almost exclusively on a reduction in alcohol sales rather than on public health. From the 40 studies which were used to justify MUP in Scotland, 32 studies had nothing to do with its impact on health – a bit surprising, given that improving health outcomes was one of its main stated objectives.

Furthermore, of the remaining 8 studies which did examine the impact of MUP on health, 7 studies came to negative or inconclusive conclusions about its health outcomes, meaning that only 1 study out of 40 had been used to justify the measure. This is a far cry from the “robustness” the report had been applauded for, particularly since the study is based on extensive modelling.

Table 1 - Reality-checked: a number of major predicted benefits of MUP were not found to have materialized according to the evidence of the Evaluation Report

Although Scotland’s First Minister, Humza Yousaf, praised MUP for “saving lives” after the report’s publication, he was later reported to the UK Statistics Office for “grossly misleading the public”. Scottish ministers were accused of “cherry-picking” statistics to portray the positive impacts the flagship policy has had on alcohol-related mortality and hospital admissions after the report’s publication, making Public Health Scotland backtrack on some of its claims.

Lack of impact on harmful drinkers, ethically problematic effects on the most vulnerable

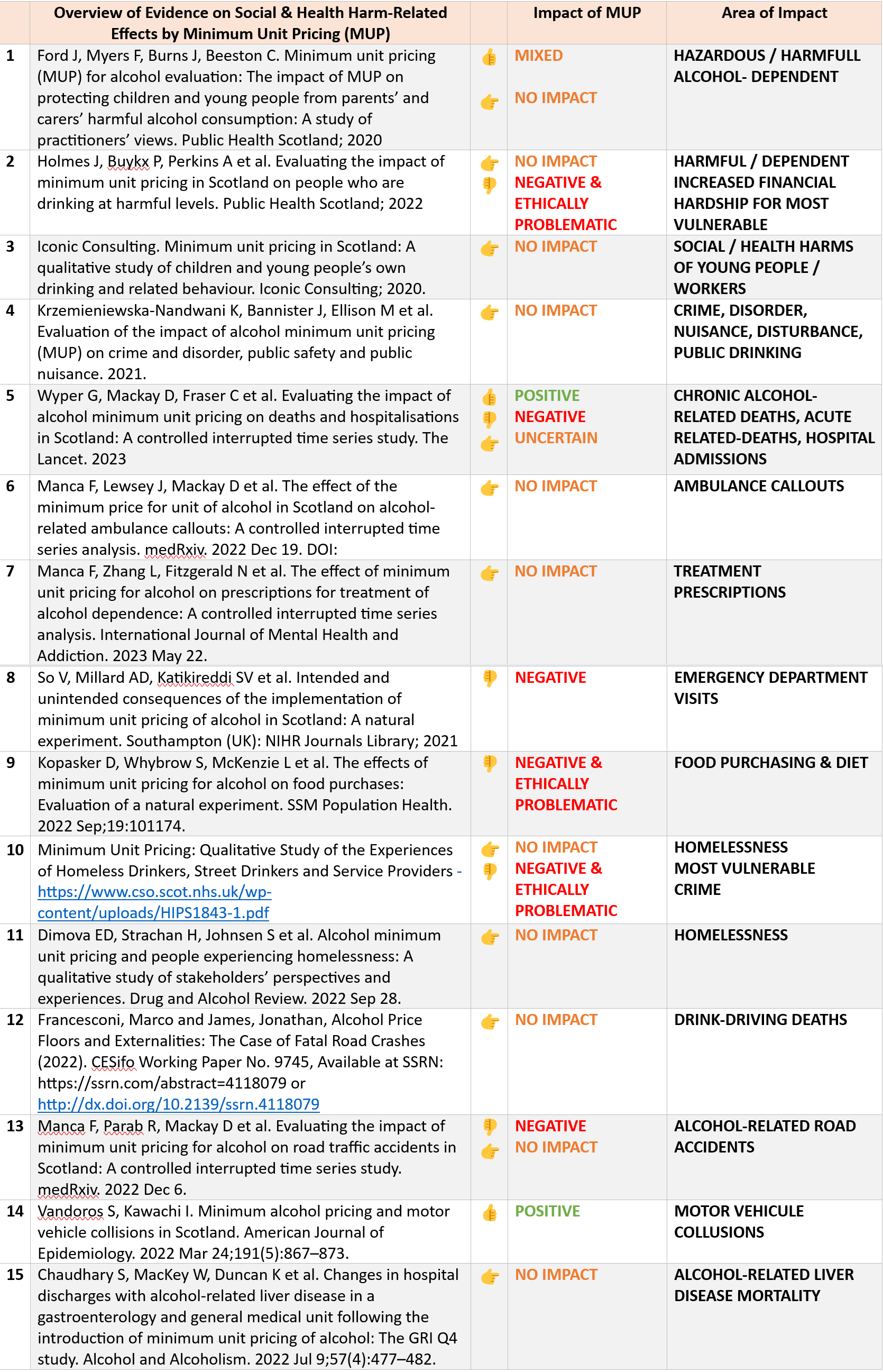

Another significant shortfall of MUP is the lack of impact on harmful drinkers, which even the authors of the model used to justify MUP acknowledged: "The results [of the report] suggest that the introduction of MUP in Scotland did not lead to a reduction in the proportion of adult drinkers consuming alcohol at harmful levels. Nor did it lead to any change in the types of alcoholic drinks consumed by this group, their drinking patterns, the frequency of drinking alone or the prevalence of harmful drinking in key subgroups."

Moreover, it also appears that one of the most vulnerable subgroups – alcohol-dependents with financial difficulties – suffered additional hardship because of MUP: "Alcohol addicts who were also financially vulnerable reported that they had had to resort to unsatisfactory strategies such as cutting back on food and, for those who were also homeless, begging or stealing to cope with rising prices". This is not a minor concern, as it makes the concept of MUP ethically problematic, too.

Table 2: Mixed bag: the evidence on the social & health-harm effects of MUP reveals a lot of ambivalence and uncertainty – and even some negative and ethically problematic aspects.

Reductions in healthy food intake

Beyond weak evidence and a lack of impact on the most vulnerable groups, it is also noteworthy to mention the negative effect on food purchases which MUP has had. After the introduction of MUP, statistically significant reductions in spending were observed in Scotland for dairy, cereals, fruit, and vegetables, while a statistically significant increase was noted for crisps and snacks. In essence, this means that healthier food choices were apparently substituted for unhealthier food choices, and it seems fair to assume that this trend would continue if the minimum unit price would be increased.

Access to treatment for dependent drinkers in Scotland declined in recent years

The doubling down on MUP is even more surprising when considering that other, fundamental alcohol-related harm-reduction measures in Scotland seemed to have failed to attract sufficient attention and funding by policymakers in recent years. For instance, access to specialist alcohol treatment in Scotland has declined by 40% over the past 10 years. In addition, 82% of dependent drinkers are not in treatment in the UK, and almost half of those who do get treatment successfully complete it.

Alcohol misuse is a complex issue and a challenge which needs to be addressed. However, blanket measures such as MUP do not seem to have the desired impact on those drinking at harmful levels, which Public Health Scotland’s report also concedes. It therefore seems unwarranted to keep MUP, let alone increase the rate to 65p. And, it would seem wiser for the Scottish government to focus on identifying the causes of harmful drinking and providing support to those who need it, rather than punishing the majority of the population who enjoy a drink in moderation.

Dr. Gregor Zwirn, Managing Director at G. Z. Research & Consulting KG and Associate to the Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge, UK